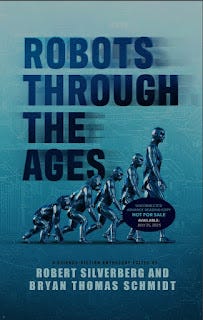

Book Review: Robots Through the Ages

A machine is a Man turned inside-out because it can describe all the details of a process, which a Man cannot, but it cannot experience that process itself as a Man can.

Months ago, I saw a travel documentary about a hotel in Japan that ran exclusively using robots. Receptionist, waiter, roomboy, chef, and laundry man—all were robots. Once you check in, you won't see a human being until you check out. It was an immensely entertaining spectacle and, at the same time, a deeply profound one. Robotics and AI are growing by leaps and bounds, but we are still unsure about the dynamics of our relationship with a non-human intelligence that doesn't need our intervention for sustenance. The only sure assumption is that our future is going to be totally and radically different from the way we have lived until now.

Robots Through the Ages is an anthology of science fiction short stories and novelettes, written by stalwarts, that deals with robots and AI. There are 17 stories in it, arranged chronologically, except for the first story, which is an original, unpublished one. There are two more original stories in the collection. From the vast ocean of good, bad, and ugly science fiction stories dealing with robots and androids, it is a daunting task to select a few that represent most of the different subgenres and also put forth relevant queries that a life with them poses. To the credit of the editors, Robert Silverberg and Bryan Thomas Schmidt, they have succeeded in their endeavour. I would rate the stories of Robots Through the Ages from above average to excellent in terms of quality, with many of them inspiring the reader to mull over the ramifications of the life-altering technological advancement that we now encounter even in our daily lives.

The book opens with a wonderful introduction to the volume by Robert Silverberg, which explains the need for such a venture. It is followed by the story Perfection by Seanan McGuire, which subtly points out the basic principle of robotics: attaining clinical perfection that is impossible for ordinary humans. It paints a grotesque picture of how an unnatural desire for perfection strips us of our humanity. Most of the stories in the collection gaze at this dilemma from different angles and in varying tones. Then we have a spooky story from 1899 by Ambrose Bierce about the creator who secretly built a machine that could think without a brain. Most of the initial stories are highly pessimistic about mixing thinking machines with human beings, like Jack Williamson's With Folded Hands, in which self-thinking humanoids that are bound to serve and guard humans wipe out the entire human industry, or Philip K. Dick's Second Variety, in which robotic warriors get so advanced that they forget which side of the war they are fighting for.

There are stories with an unpredictable twist in the last sentence, like Goodnight, Mr. James by Clifford D. Simak, in which a clone has to think of saving his skin while trying to kill a runaway murderous telepathic alien, and Instinct by Lester del Rey, which is about a robot in an apocalyptic world hell-bent on cloning a man, going against its superior, but having no idea what to do with him once cloned. A Bad Day for Sales is a satire about an automatic robotic vending machine finding himself in a nuclear blast. Another laugh-out-loud story is The Golem by Avram Davidson, which is about a robotic demon with murderous intentions and a retired couple who don't give a hoot. For A Breath I Tarry by Roger Zelazny is a profound existential thriller about a sentient machine that probes what it is to be a man in an apocalyptic future, with a beautiful ending.

The editor of the book, Robert Silverberg, has contributed an interesting and humorous story titled Pleasent News From the Vatican, about a group of people waiting for the election of a new pope with the possibility of a robot being elected. That Must Be Them Now is a story about a lowly robotic junk-collecting drone with ambition trying to hustle his way up against formidable competitors. There is a humorous play by Suzanne Palmer titled R.U.R.-8? (referring to Karl Capek's play R.U.R. that introduced the word robots) about the introduction of robots making humans too lazy to pursue anything meaningful. Today I Know by Martin L. Shoemaker is a wonderful, warm, and feel-good story that is the most recent one in the collection, about the relationship between an empathetic robot and a suicidal girl.

There are certain stories that did not work as well for me as the ones that I mentioned above, though even in them I could spot flashes of great imagination and genius. Dilemma by Conie Willis felt like a fan fiction story about Asimov, though it is eminently readable. The Robot's Girl by Brenda Cooper, which dealt with a couple trying to rescue a girl in their neighbourhood who is brought up by robots alone, was repetitive and ended up as an ordinary story. The climactic twist in Robinson Calculator by Paul Levinson didn't work for me, though the story until then was delightful. Ken Scholes has contributed an original story titled Of Homeward Dreams And Fallen Seeds And Melodies By Moonlight, which is a prequel to the world he created in his novel series. I feel someone who is more familiar with the lore will appreciate it more.

I believe we are at a crossroads as humans, and the possibilities and dangers of our next step forward are to be known, discussed, and resolved by the time we traverse the point of no return. Robots Through the Ages works as a collection of short stories due to its sheer diversity of themes, which make the reader think about the issues and opportunities created by a technology that has the power to permeate every dimension of human life.