Literature, Faith and Politics: Dostoevsky Through Critical Eyes

Dostoevsky is either the compassionate friend of the insulted and injured or the dreamer of weird dreams, the dissector of sick souls.

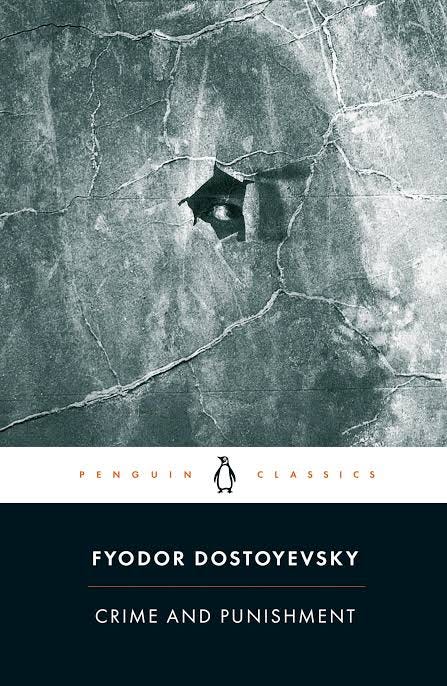

My first reading of Dostoevsky was an abridged version of Crime and Punishment in Malayalam. Even though it was a very simplified version, it was enough to move a high school student and make him wonder about the mysterious workings of the human mind. Later I read a translation of The Brothers Karamazov and some of his short stories. Among the many classics that I read in those times, there was something that set this writer and his works apart. Though the world has stormed past, the books of Dostoevsky are still read and revered with the same zeal with which they were read during nineteenth-century Russia.

It doesn't mean that the books aren't aged. Some of his philosophical views, his thoughts on faith, and his thoughts about political ideologies have become obsolete in the new age. But certain aspects, like his insightful portrayal of human psychology, the literary quality of the works, and the clinically precise portrayal of 'underground,' are as relevant today as then. The success of Dostoevsky is that, while many of his contemporaries are read today as examples of the relics of the past, the present generation turns to him as a writer to be taken seriously. Though some may be turned off by the unbearable tales of despair, a large portion of his new readers are able to appreciate his writings.

The perpetual ill fortunes that Dostoevsky had to endure in his eventful life are also instrumental in his continuing popularity. Sharp reflections of these incidents in his works have created a prophetic aura around him. His father's murder, his death sentence and the last-minute pardon, banishment to Siberia with only a copy of the New Testament allowed to be read for three years, his descent into gambling addiction and severe economic difficulties—all are used in his works, mostly metamorphosized as spiritual or metaphysical portrayals. All his major characters give voices to the debates running in his mind about faith, religions, and ideologies.

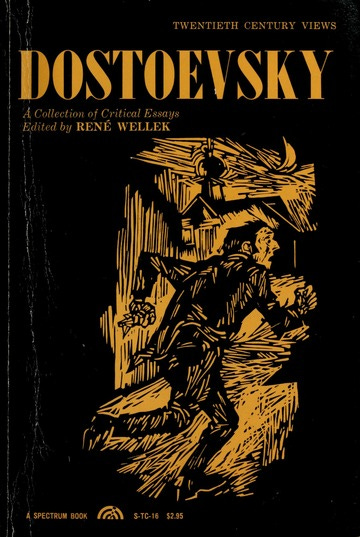

Dostoevsky: A Collection of Critical Essays is a book edited by René Wellek and published as part of the series Twentieth Century Views by Prentice-Hall in 1962. The book contains eleven essays about Dostoevsky written by different scholars of different times and nationalities and includes an introduction by Wellek, in which he tries to give us a sense of the structure and purpose of the book. Experts of philosophy, literature, theology, psychology, politics, and psychoanalysis examine the life and works of the writer to create a three-dimensional analysis of the enigma that's Dostoevsky.

The book opens with the brilliant introduction of the editor that sheds light on the history of the criticism of Dostoevsky. His early recognition and later backlash in Russia, evolution into a prophet and subsequent fall from grace during the initial Bolshevik period, final ascent as an important part of Russian literature in later times, and how almost all of Russian efforts, be it Marxist or the émigré writers, grossly misunderstood him are portrayed in detail. We see him read differently and mostly erroneously in Germany, France, Britain, and the US. This essay itself makes the reading of the book worthwhile for its summarization of the efforts to evaluate the writer and the editor's own perceptive notes about him.

The first essay by Philip Rahv is about Crime and Punishment. Rahv explores the classic and comes up with observations that are invaluable in understanding the beauty of it. He dissects the structure, pace, and content of the novel. Beginning with how the entire novel structurally concentrates on the titular crime, he analyzes its narrative pace, which he finds extraordinary. He explains the unique manner in which the protagonist's consciousness is excluded from everything that's not pertaining to his situation and why the writer chose not to reveal the exact motive behind the crime.

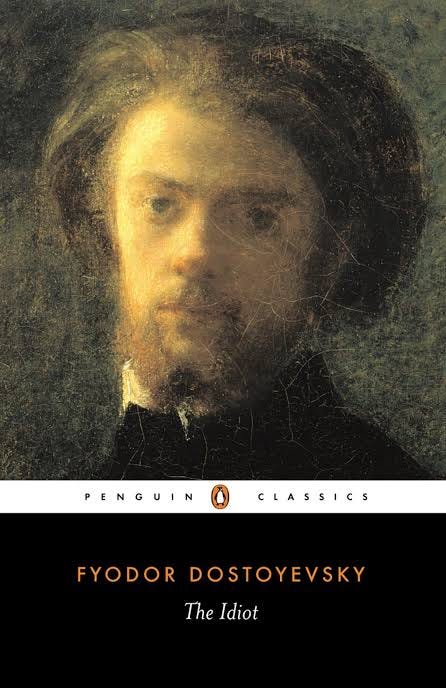

The second essay by Murray Krieger is an analysis of the novel The Idiot. It is as surgical and insightful as the former one and also goes in depth to understand the questions about faith that Dostoevsky asks through Prince Mishkin, the titular idiot, and his other characters. He explains how the writer, who intended to portray a truly beautiful soul with the protagonist, fails to do so. But that failure is not a creative one, and as a result we get another complex character and a plot that portrays 'the desperate struggle for personal human dignity.'

In his essay, Irving Howe argues how Dostoevsky is not a political writer. Though his works contain strong political discourses, they essentially form the background of deeper philosophical and spiritual crises. His works are primarily about the 'Russian destiny,' which is inseparable from the Orthodox church, and his politics are "nonsocial, and hence apocalyptic." Though he mentions several of his works, Howe uses the novel The Possessed to elaborate his points.

Eliseo Vivas identifies the complexity of the faith of Dostoevsky through The Brothers Karamazov. He exposes how it's not a 'logically simple structure' but 'a heterogeneous mass of living insights.' He asks us to be careful while going through his works looking for doctrines, because they contain 'dramatic organization of life.' He writes about the insights that the author adds to our knowledge of the human soul and claims that Dostoevsky anticipated Freud. He explains how The Brothers Karamazov shows an exhibition of characters of every ideological and religious prototype that existed at his time.

The collection features 'The Preface to The Grand Inquisitor' by D. H. Lawrence, in which he explains how he was progressively devastated each time he read this portion of The Brothers Karamazov, which also exists as an independent book. He uses a more personal tone rather than the analytical style of others. He sees the author's opinion on Christ in the book, which is that Jesus is inadequate and needs men to correct him. Dostoevsky proclaims that men can never be free because it's in their nature to demand miracle, mystery, and authority, which prevent them from being free. Those who are capable of abstaining from these are essentially gods.

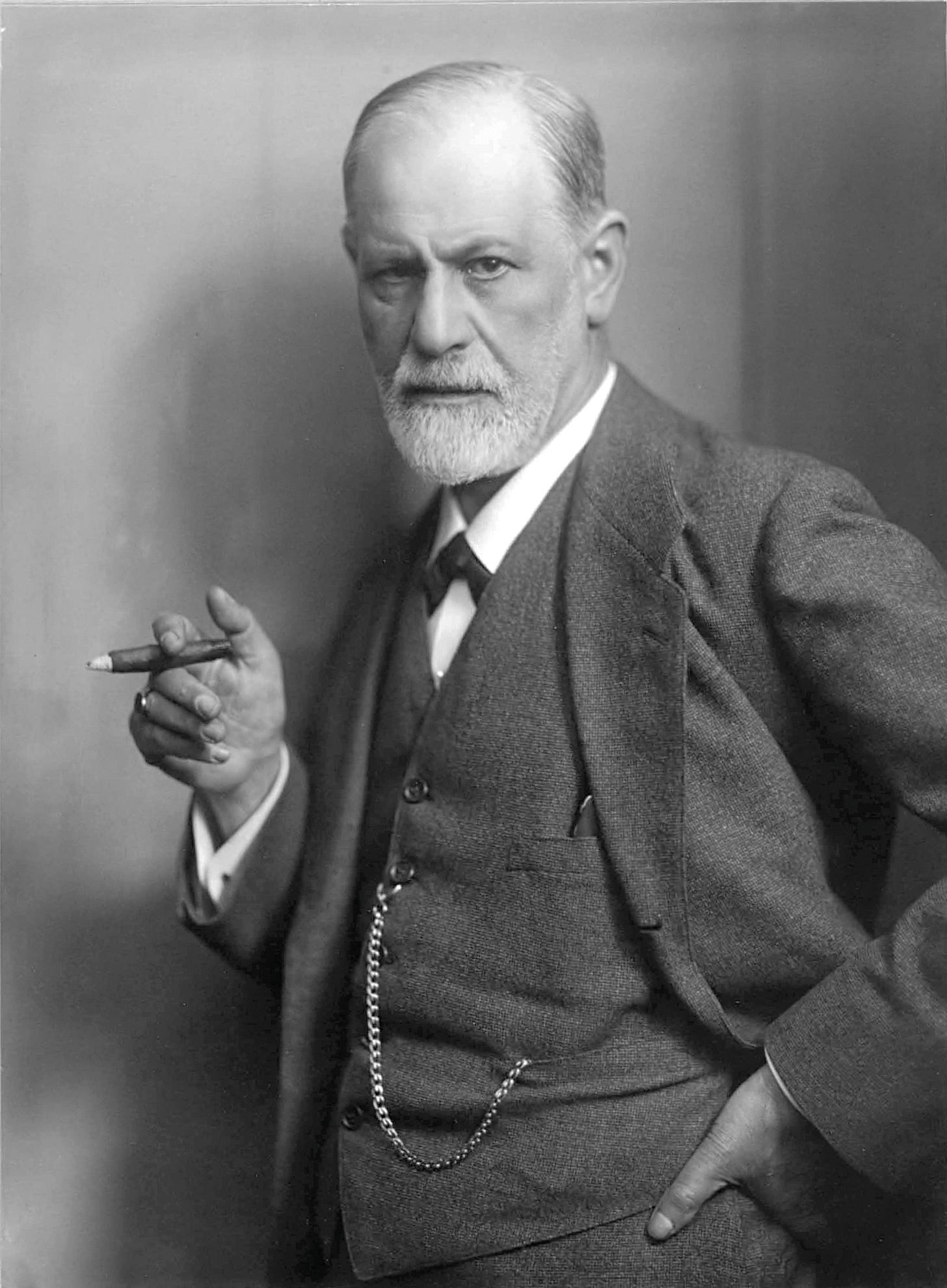

There is an attempt to psychoanalyze Dostoevsky from none other than Sigmund Freud through his essay 'Dostoevsky and Parricide.’ As expected, he was quick to put the blame on his father, who was murdered in his childhood, for all the troubles of the author. Yet in his essay, you may find a few insights about the writer and a few keys that could help you unlock the mystery of his books. The major one among them is the connection of the epileptic episodes of Dostoevsky with some dimensions of his works, especially dreams, that may seem supernatural. He also sheds light on the issue of parricide that turns up in his works, especially The Brothers Karamazov.

In his essay Dmitri Chizhevsky analyzes the repetitive appearances of doubles or doppelgangers in the works of Dostoevsky. Established at first in the novel The Doubles, which was a critical disaster that affected him, the concept became central to his bibliography, giving it deeper moral and psychological dimensions. In his works we frequently find pairs of characters who reflect each other while representing opposing ideologies.

The piece by V. V. Zenkovsky tries to decipher the author's religious and philosophical views. It elaborates his religious views as not dogmatic, but more experiential and rooted in redemption through suffering. The essay analyzes his philosophical outlook, 'anthropocentric,' and establishes that for him, man was the most important while also the most dreadful, which is more similar to ancient Christian belief than the present systematic one. Zenkovsky believes that "Dostoevsky's faith in man... triumphs despite his immersion in the darkest impulses of the human soul."

Georg Lukács offers a Marxist interpretation of the author's works. He argues that Dostoevsky should be seen as a realist in spite of his existential and metaphysical themes because he portrays the real contradictions of social life. Lukács addresses Raskolnikov's crime as an experiment with Napoleonic ambitions, which ultimately risks the moral existence of the experimenter. The writer finds out the connection between Balzac and Raskolnikov, though the theme of Crime and Punishment 'is just as original, stimulating, and prophetic.' He shows how the theme is echoed in several other works in different forms. He explains how the despair of his characters stops being just a trivial spice of life and becomes 'an actual banging at closed doors.'

The final essay of the collection by D. A. Traversi concerns the metaphysical elements in the works of Dostoevsky. He says that interpretation of Dostoevsky using abstractive ideas won't be as effective as using the real text. He explains how sensual experiences are frequently portrayed in his works in an attempt to transcend the senses. He uses sensibility 'as an instrument to attain independence from everything distinctively human.' The essay further elaborates this metaphysical exploration using physical senses.

The book Dostoevsky: A Collection of Critical Essays impresses the reader with the wide variety of its contributors. We find them from different times, from different countries, reading the books through different languages, and expressing different ideological viewpoints. Many of the essays criticize Dostoevsky's works, life, and ideological stands, and many times their contradictory nature. We find these contributors confused with how to frame him as part of literary history. This confusion among critics, I believe, is the aspect that keeps Dostoevsky interesting, relevant, and important in every period of human history. The book gives a three-dimensional perspective of the author and provides an interesting experience of viewing his life and works through multiple viewpoints.