Wanderers, Kings, Merchants by Peggy Mohan: A Linguistic Excavation

A book about deep diving into languages and uncovering a forgotten past.

Through much of our history, India has been known for precisely that: a huge number of little dialects and languages that overlap with regional languages of literacy and the market, with one big language in prime position at the top, marking out the reach of the empire.

A unique quality that differentiates human beings from other animals is our capacity to use languages. We rely on complex languages for communication and to record and transfer them as knowledge and information. Languages are the pillars of human civilization that enable us to populate and prosper, explore new frontiers, and fight adversities. As humans evolved civilizationally and culturally, languages also evolved, merging and demerging, changing themselves and transforming others, eventually becoming a coded blueprint of human history. By decoding the evolution of languages, it is possible to excavate our forgotten annals of the past.

"Wanderers, Kings, Merchants" is such an attempt by the renowned linguist Peggy Mohan, where she tries to uncover the different ways in which human interactions happened in the Indian subcontinent in its past. She inspects the older languages from the available texts and documents from different points of history and does a comparison with the present form to find clues that could indicate the patterns of human movement inward, outward, and within the subcontinent. This in turn gives us new perspectives on history, which may even challenge several preconceived notions among the public and even the academia.

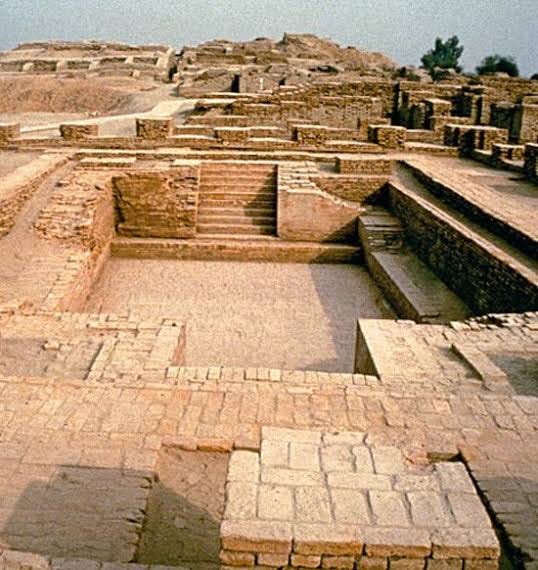

The writer begins her journey during the Harappan civilization, and in each successive chapter discusses a different time and place where an outsider group merged with the locals and disrupted the status quo, thereby diverting history on an alternative route. It's strange to observe a pattern repeating in most of these events. The invaders, mostly males, appear in a locality and take up local women as wives. They establish their language as official and relegate the local languages and dialects to the periphery. But kids born to local women learn their mothers' language when small and later progress to the stronger master language of their fathers.

Thus the master language starts acquiring many characteristics of the local language, and within a few generations, these changes are established officially in literature and documents. The writer establishes the same trend repeating multiple times throughout history with minor differences. While Sanskrit, Persian, and English were imported from outside by invading forces, the local dialects and languages, especially the Dravidian, Prakrit, and many minor languages, which are sidelined, serve as substratum by retaining their grammar and vocabulary of the master language grafted to it.

The book is successful in captivating the imagination of its readers by explaining complex topics in an accessible manner. I am particularly thankful for the brilliant examples that she comes up with, which were instrumental in cementing certain important concepts in the mind of the readers, like that of the tiramisu bear. She interweaves personal anecdotes, historical events, and scholarly information in her narration, which makes the concepts more intelligible and relatable. The book also makes us introspect our own language, pronunciation, and grammar through a linguistic perspective.

Even when it's a perspective-building read, there were a few instances where I felt the writer was jumping the gun to conclude. Otherwise, she neglected to provide enough clarification for certain aspects of her solution. For example, she derived that the kind of Sanskrit spoken by men and women had differences with an example from "Abhijñānaśākuntalam" by Kalidasa, in which Sakunthala, the female protagonist, speaks in a different accent. But it's not specified if there is a male character from the same location who speaks proper Sanskrit. We cannot expect the father of Sakunthala to not speak anything less than perfect, because he is depicted as a knowledgeable sage. It could be that Sakunthala, along with other characters, both male and female, are speaking the same dialect. It would have been helpful if the writer had taken care to clarify such issues.

Despite such minor issues, the book is a thought-provoking read that could alter some of the rooted conventional misconceptions about the complex linguistic history of the Indian subcontinent. It will be beneficial for anyone interested in Indian history, languages, and heritage.

I came across your substack by chance and then this post as I was browsing through the archives! A good introduction to Peggy's book.

Incidentally, I've translated this book to Kannada, which got published earlier this year. It's getting a lot of appreciation and is steadily building a niche readership.

Have subscribed to your substack. Here's wishing more power to your elbow!

Quite interesting, Sakunthala's point did not strike me then. Peggy Mohan mention about the book 'Early Indians' by Tony Joseph, couple of time in her book, and that prompted me to get a copy. Reading that gives much more clarity to the subject.